VIDEO TECHNIQUES

BEFORE YOU BEGIN

There are a few how-to-be-a-multimedia-journalist articles that are required reading for any aspiring new media journalist.

You aren't allowed pass GO and collect your $200 unless you take the time to familiarize yourself with these essential readings from the new media canon (according to us.)

The list is always growing and there are arguably many more entries that should be on this list. So if you feel we've missed something, let us know and we'll consider adding it to the list. In no particular order - as they're all equally important:

- How to Stop Worrying and Learn to Love the Internet By Douglas Adams

- The leaked New York Times innovation report is one of the key documents of this media age

- Adam Westbrook on Web Video Problem

- Ira Glass on taste

STAYING IN THE KNOW

Subscribe to the email newsletters for each of these sites. You won't be disappointed as they are the best in each respective discipline. I guarantee they'll keep you informed and updated on all the latest news, gear and best practices.

- FILM / VIDEO: No Film School

- PHOTOGRAPHY: Petapixel

- DESIGN: io

- JOURNALISM INDUSTRY: American Press Institute

- CREATIVE LIFE: Brainpickings

- BE SMARTER: org

INTRODUCTION:

Let’s start at the very beginning – a very good place to start!

People invariably make the same sets of mistakes when they first start shooting video:

- Trees or telephone poles sticking out of the back of someone's head

- Interview subjects who are just darkened blurs because there was bright light in the background

- Boring shots of buildings with no action

Here are some shooting tips to help you avoid some of these common mistakes.

We recommend that you go out and shoot some video first, and then read through these tips while reviewing your footage to drive home what you need to avoid.

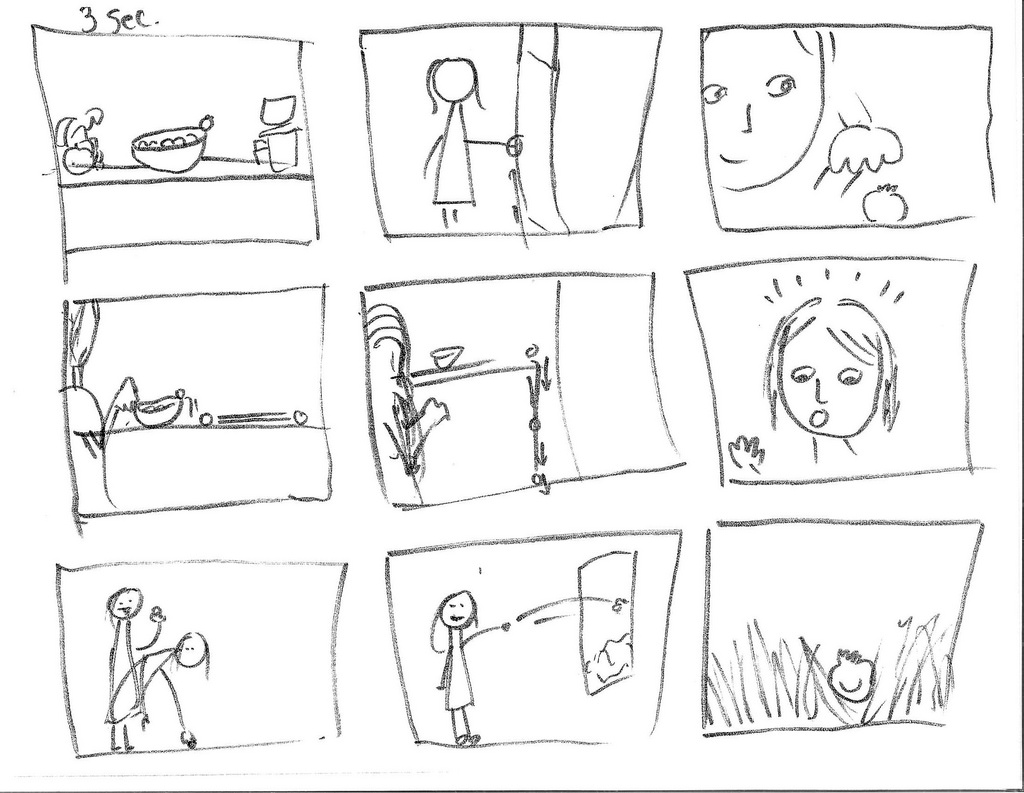

PLANNING YOUR SHOOT - Preparation is key

- To prepare for the shoot - Write the story out before you begin production, do this by listing the elements both video and audio you want to gather to tell the story story.

- Talk over your shoot with other members of the production team and make sure you're clear on what the story is and what shots you need to tell the story.

- Think about what's going to look good visually, and how your shots are going to come together sequentially to tell that story.

So if you imagine that your piece is a skeleton, then the video and audio you shoot or record is the flesh that will cover the skeleton to show or tell that story.

CHECK YOUR AUDIO

Be sure to plug a set of headphones into the camera or recording device to check your audio - make sure you're getting an audio feed.

It's easy to forget to plug an audio cord into the camera or to properly set the audio level – and wind up with great video but no audio to accompany it. Audio is just as important for your final film as your video.

Finding the right Mic for your production.

SHOOT SELECTIVELY

Framing your shot image.

Think before you shoot and avoid over shooting. This will come in handy when you are editing or working with an editor. Be aware of what you're shooting and when the camera is recording. Don't record unless you're taking a shot.

For example, don't record when you're changing from one shot to another or focusing. Wait until you have the shot you want to record and then press record.

That way you'll save a huge amount of time later when you're capturing your video into a computer and you won't have to go through a hour-long footage to find the 20 minutes of shots you want.

And you'll save money by being strategic in the way you gather shots.

Consider the circumstances you are recording if you are in an event and you need to move fast – shooting accordingly.

SHUT UP WHEN YOU SHOOT

When you press the record button, shut up already!

Keep in mind that when the camera is rolling it picks up all the ambient sound, not just what you're focusing on. And you won't be able to separate the unwanted audio out in the editing process.

Don't talk while the camera is rolling, either to yourself or with other members of your team, and no humming or chewing gum.

This is especially important when you're shooting B-roll like natural sound, such as the noise of a busy street or a nature scene, where the sound is critical to the shot.

Also remember to not talk over your subject/participants response to your questions.

HOLD ON YOUR SHOTS

Hold your shots for at least 15 seconds, before you pan, zoom or go onto another shot.

That way you'll be sure you have enough video of a scene to work with later when you do your editing.

When you're starting out, silently count out the 15 seconds to yourself – "1,000 and one, 1,000 and two, 1,000 and three…" – to make sure you've held a shot long enough.

Remember that you can always take a 15-second clip and make it a 2-second clip during editing, but you can't take a 2-second clip and make it into a 15-second clip.

EXCESSIVE PANNING AND ZOOMING

Don't constantly pan from side to side or zoom in and out with the camera – hold your shots and look for the one moment that's really captivating.

If you're constantly panning and zooming, the one shot you'll really want to use will lose its impact with all the movement by the camera.

Instead start with a static, wide angle shot, and hold it for 15 seconds.

Then make your move to zoom in or pan, and hold the next static shot for an additional 15 seconds.

This will give you three usable shots – the wide-angle, the close-up and the zoom in between – to choose from in the edit room.

This is especially important for video you're using on a Web site because video with a lot of movement – such as what's created with panning and zooming – doesn’t display well on the Web. Video clips need to be compressed to play on the Web, and that means if there's lots of movement in your clip – such as pans and zooms – it will appear choppy and slow.

Similarly, to get a close-up it's better to keep your camera set to a more wide-angle view and move the camera closer to the subject of your shot, than to have the camera farther away and zoom in for the close-up. A telephoto shot using the zoom feature will accentuate movement by the subject and make the shot appear shaky.

SHOOT IN SEQUENCES

This is especially true when shooting B-roll such as crowd scenes or nature shots, rather than a static shot of an interview with someone.

Remember that you will be determining what the viewer sees and how the story unfolds, so try to shoot discrete segments that you then can assemble into that story when you're editing.

Here's an example:

Think of different scenes, as in a movie. Each of those scenes is made up of sequences. In each sequence, you need to follow the action, and shoot wide, medium and close-up.

Say you want to capture a person arriving at work in the morning on her bicycle — that's one sequence. It could be made up of the following shots: the person pulling up to the building, getting off the bicycle, chaining the bicycle to the bicycle stand, taking off gloves, taking off her helmet, tucking gloves into the helmet, and walking into the building. Every little detail is important. You can't shoot enough details.

In fact, a good ratio to shoot for (literally) is 50 percent closeups and extreme closeups, 25 percent medium shots, and 25 percent wide shots.

It might break down like this: a wide shot of her arriving. A medium shot of her getting off the bicycle. A close-up of her pushing the front wheel of the bike into the bike stand. A close-up of her chaining the bike to the stand. An extreme closeup of her taking off her gloves. An extreme close-up of her eyes as she looks at her hands while she's taking off her gloves. A close-up of her taking off her helmet and tucking the gloves into it. A close-up of her straightening her hair and looking at the building. A medium and wide shots of her walking into the building with the helmet tucked under her arm.

Framing and Composing Your Shots

Be aware of composition in your shots and how you frame your shots, particularly with interviews.

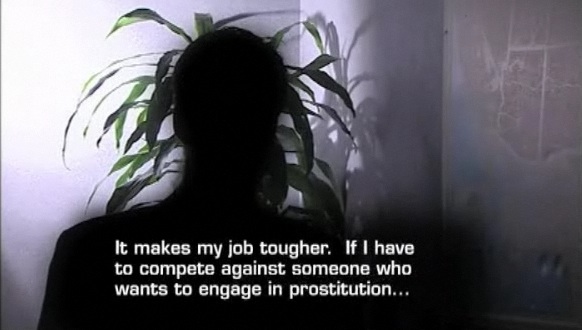

For example, avoid a shot of a person with a plant or pole in back of them. It will look like the plant or pole is growing out of the back of the person's head.

This interview setup had a distracting plant coming out of the anonymous source's head.

When shooting interviews pay attention to your surroundings and don't be reticent or shy about rearranging furniture, moving things on a desk, pushing plants out of the frame of your shot,. etc. to improve the setting, or asking the subject of your shoot to change positions so you properly frame the shot.

And if you're having technical problems, don't be afraid to take charge and stop the interview until you can properly set up the shot.

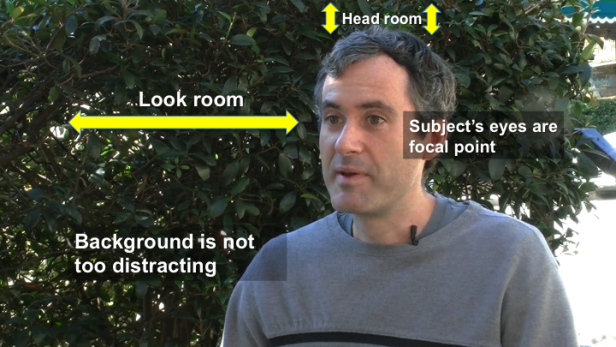

HEADROOM AND NOSEROOM

Leave the proper amount of noseroom and headroom in front of and above the person you're shooting.

For example, don't have a shot where there's excessive empty space above a person's head. That's just dead space. There should be just a little room above a person's head in a shot.

It's better to have that room below the person's face, space you then could use when you're editing the video to add a title with the person's name.

But don't have the shot too low where you crop the top of the person's head.

And if you're shooting a person standing, don't chop them off at the knees – get their entire body in the shot..

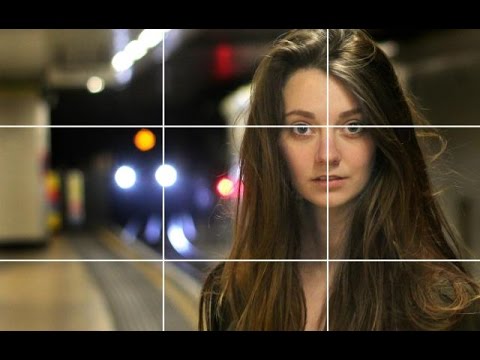

One approach is the rule of thirds:

- one third of the frame should be above the person's eyes

- one third of the frame should be the person's face and shoulder area

- one third of the frame should be the person's lower torso.

And if the person is looking to the side, add space in the direction in which the person is looking, in front of their nose.

DEPTH OF FIELD

Be aware of ways to increase the sense of depth within your shot, since video images are inherently flat.

If you're shooting someone, try to include other objects in the background or foreground that give the viewer a sense of depth. That way the interview subject won't appear to be just a two-dimensional object on the screen.

Also remember that a wide angle shot will provide a much better depth of field than a telephoto shot where you've zoomed in on your subject.

How Lens Change the Depth Perception

The focal length of the lens not only changes the angle of view, but also affects the foreground-background relationship. When zoomed in from afar, the background will appear compressed with the foreground, and a wide angle will make the background appear farther away. This phenomenon is called Perspective Distortion.

CHANGE ANGLES AND PERSPECTIVES

Try to change point and/or angle of view after every shot. Look for interesting perspectives.

Don't shoot everything from eye level – it's boring.

Especially try shots where you hold your camera close to the ground and shoot up toward your subject. The small size of digital video cameras makes these shots very easy to take.

For example, if you're shooting a scene like people walking on a sidewalk, hold the camera low to show their feet moving, rather than straight-on shots of their faces.

Or if you're shooting someone working at a computer terminal, take one shot from over their shoulder, then another that is a close-up of their hands and fingers using the keyboard and mouse, then a shot from over the person's other shoulder, then a low angle shot looking up at them and then a facial shot.

Or hold your camera above your head to get a different perspective on a scene.

Do a close up shot, because that often provides a more intimate view of a person. This is especially important with video on the Web, because the video viewers use small windows and wide-angle shots won't display much detail.

Don't just rely on zooms to get these different perspectives – move the camera closer or farther away.

If you take shots from these different perspectives, when you edit your video you'll be able to put together a sequence of 4- or 5-second shots of your subject, rather than one 20-second shot from a single perspective.

GET PEOPLE IN YOUR SCENES

Try to get people in your shots, which almost always makes the video more interesting.

Don't do a static shot of the front of a building – try to include people walking in and out to animate the scene.

TRIPODS FOR STEADY SHOTS

Use a tripod to get a steady shot, particularly if you're shooting something that is not moving or a formal interview.

If you don't have a tripod or you're doing a shot where you'll have to move quickly, then find something to steady your camera – i.e. lean against a tree, put the camera on top of a trashcan, etc.

If you must shoot without a tripod or other support, shoot a wider angle shot. The wider the focal length, the steadier the shot.

ANTICIPATE ACTION

Anticipate action by trying to predict where the subject/action will go, and then be ready to shoot it when it moves into the frame of your shot. Think ahead and get positioned for the action that's to come.

Let action happen within the frame. Don't constantly move the camera in an futile attempt to catch everything.

And don't be afraid to allow your subject to move out of frame, rather than trying to follow them with your camera.

This is especially important if you're taking a shot of a person who is walking and then later another shot of the person sitting down.

If you follow the person while they walk with your first shot and always keep them in frame, and then cut to second shot of the person sitting down, it can create a mental disconnect for the viewer as to how the person got to the second position.

If instead you show them walking out of the frame in the first shot, then it's logical to the viewer that the person would be seen in the next shot sitting somewhere else.

Vimeo post on framing and composition.

INTERVIEWS

Ask the person you're interviewing to look at you, not at the camera.

Try to avoid a straight-on shot – shoot the person from a slight angle to the left or right.

Don't use the zoom feature to get a close-up shot of the person – that accentuates movement. Instead, move the camera a little closer to the subject.

Don't have your interviewee sit in a chair with wheels or that squeaks.

And watch out for nervous activity that creates noise – like someone jangling change or keys in their pocket. Stop your shoot, point it out to them, and then start shooting again.

Don't do a pre-interview off camera where you tell them the questions you'll be asking beforehand. It makes them sound stilted and canned in their responses when the real interview begins. Just give them a general idea of what you'll be discussing.

When you start the interview, have the camera roll for a few seconds before you ask your first question.

And during the interview, relax and listen. Don't nod or make gestures.

SIT - DOWN INTERVIEWS

When doing a sit-down interview with a subject where the reporter will be asking questions of the person, start with a set-up shot from behind and to one side or the other of the reporter that focuses on the person talking while the questions are asked.

Because this shot will show the person at an angle, leave extra room in the shot in the direction the person is looking (rather than centering the person in the middle of the frame).

Then do a wider angle shot from the same position that includes the reporter while the subject of the interview is responding to a question.

Finally, move your camera to get a frontal shot of the reporter listening to the person – which is called a reverse shot or cut-away. This is shot from behind the person being interviewed. And again get both a close-up and a wider angle shot.

It's important that in this reverse or cut-away shot, you position the camera on the same side of the room as it was when you did the first shot from behind the reporter.

So visualize that there's an axis that runs from the interviewee to the reporter. When you are taking your first shot from behind and to one side of the reporter, stay on the same side of that axis when you move the camera to do the front-on shot of the reporter.

You generally do not film the reporter actually asking the questions – just the answers of the interviewee and/or the reporter listening while the questions are answered.

MICROPHONES

If you're using a hand-held microphone, you usually should hold it about 5-6 inches below the interview subject's mouth.

Don't hold the mic right in front of the person's mouth, but slightly off to the side and tilted toward the mouth. This will help avoid picking up "popping" noises from a person's lips as he/she speaks.

Tell the interview subject to try to ignore the mic and concentrate on the camera.

If it's noisy, then use a lavalier clip-on microphone to reduce the ambient sound.

But watch for necklaces or chains on a person's neck, or buttons on a shirt, that could rub against the lav mic and create noise.

With a lav mic, you'll need to "dress the mic" – properly attach it to the person you're interviewing

Ask the person to run the cord to the lav mic up the inside of their shirt (so the wire won't show in your video).

Then clip the mic to the outside of their shirt, about 5-6 inches below their mouth. Try to center the mic as much as possible. If you have it too far to one side, it won't pick up the audio well if the person then tilts his/her head to the other side while talking.

Use this same procedure if the person is wearing a t-shirt, running the cord up under the shirt and clipping the mic near the top of the shirt.

If the person has a necktie, run the wire down the back of the necktie and through the little label on the bottom back of the necktie.

If it's windy, the lav mic will pick up the sound of the wind. In this case try to clip the mic closer to the person's mouth, or switch to a hand-held microphone with a windscreen on it that muffles the noise of the wind.

AVOID HIGH CONTRAST IN LIGHTING SITUATIONS

Avoid shots of areas that have high contrast such as dark versus light settings, or bright sunlight and shadows.

For example, don't place an interview subject against a bright window or white wall or with sunlight behind the person.

This back light is problematic for the automatic exposure feature of the camera. If the camera focuses on the light in the background, then the face of the subject will be darkened and indistinguishable. If the camera focuses on the person's face, then the background will be washed out in light.

It's usually best to shoot with the sun to your back.

If the sun is directly overhead, hold your hand over the top edge of the camera lens. This will in effect extend the sun screen and avoid having the camera misread the amount of sunlight.

CHECK WHITE BALANCE

White balance has to do with differences in color caused by the intensity or "temperature" of light and how a video camera compensates for these differences in color.

Sunlight is rarely pure white, but rather takes on different shades, such as a yellow or orange tinge at sunrise and sunset, or a blue tinge in a shaded area. Sunlight also has a different color temperature than artificial light.

Digital video cameras usually come with an automatic white balance meter that essentially tells the camera which intensity of the color white is in the picture, and the rest of the colors in the spectrum are adjusted accordingly to make the video look as natural as possible.

But there are cases where a video camera may misconstrue the intensity of the lighting because it is measuring the general intensity of the light it sees at the spot where the camera is located rather than the intensity of the light at the location of the subject of your shot.

The result is either a blue or orange tint to the video you shoot.

For example, if your camera is in bright light, but the subject of your shot is in the shade, the camera will be reading the light as more yellow in tone because the camera is in yellowish sunlight. The subject of your shot thus will come out looking slightly blue, because the subject is actually lit by bluish shade light.

Or your camera may be in a room where the intensity of the light is from an artificial source like fluorescent lamps, but your subject is next to a window and in sunlight. In this situation you also will have a white balance problem.

To fix this, you need to hold up a piece of white paper next to the subject of your shot, and then zoom the camera in on that white paper. Then push or select the white balance button on your camera to set the proper white balance at the position of your subject.

The camera essentially is forced to look at a true white color at the location of the piece of paper, and then balance the rest of the color spectrum around that true white that it sees.

Video cameras also usually come with white balance pre-sets, such as artificial light or natural sunlight.

MANUAL EXPOSURE

The auto exposure on digital video cameras is generally very good at setting the correct lighting. And most difficult lighting situations should be solved first by changing the position of the camera or the subject – such as not shooting into direct sunlight.

But there are occasions when you'll need to manually adjust the exposure on your camera.

One example is on a bright day where there's lots of movement and light contrast in front of your camera, such as buses passing by with large billboards on their sides that reflect the bright sunlight. The camer then will open and close its exposure in response to these changes.

Or if you have to take a shot of a person from a certain angle, and there is bright light behind the person.

In these cases, aim your camera at the light setting you want for your shot and then switch from auto to manual exposure.

For example, if you're shooting an interview with someone, zoom in on the person's face, hold the shot there and then switch from auto to manual exposure.

The camera then will retain or lock in whatever setting you selected throughout your shoot, despite any changes in the lighting.

GET ALL THE SHOTS YOU NEED

Make sure you get all the requisite set-up shots, cut-aways, and so on, even if you don't think you'll use them. They may come in handy in the edit room.

So start with an establishing shot – such as video of the person who is the subject of your story – and then remember to get the other kinds of shots you may use to supplement that in your final film.

The latter is called B-roll, which refers to the earlier days of film when you had two rolls of film – A and B – and you had to edit them together.

A-roll is the main subject of your shot, invariably with audio such as an interview with someone. B-roll is the background video for your film, often just video over which you'll lay an audio track (such as the person talking in the A-roll). So don't forget to shoot a variety of B-roll.

Another type of shot to look for is natural sound (called "nat sound"). This is film that has some natural background noise – traffic on a street, birds chirping in a park, etc. This audio can add depth and impact to a two-dimensional video footage.

Labeling and organizing your footage for post-production is of the utmost importance

-

Ingest the cards CF/SD cards onto your drive.

-

Make sure to make a copy of the footage for safety and redundancy.

-

Put footage in individual folders labeled by day and subject matter.

-

(JOHN SMITH RODEO PIECE) >

-

(FOOTAGE) >

-

(CARD 1_Day 1_10_5_16) >

-

(VIDEO John Smith, 10_5_16_Day in life of RODEO KING)

-

(AUDIO John Smith, 10_15_16_Day in life of RODEO KING)

-

(Card 1_Day 2_10_12_16) >

-

(VIDEO John Smith, 10_12_16_Preps for Rodeo Competition)

-

(AUDIO John Smith, 1012_16 Preps for Rodeo Competition)

Video – make sure to keep the video and audio that correspond together for the same shoot together in the same folder so it will make it easier to sift through when you start working with it in post-production. Audio

When you are doing a shoot that requires more than one CF/SD card, be sure to label each CF/SD card at the scene. And pick a label that will make it easy to identify later.

There's nothing more frustrating that starting to edit and not knowing which CF/SD card folder is of which shot or what is in each CF/SD card folder.

You can shift the little white switch on a CF/SD card from record mode to save mode to help you stay organized. Once you move that tab you know that card is full and you can move on to the next card to use for filming.

ABOUT THIS TUTORIAL

This tutorial is based on lectures of Richard Koci Hernandez, and formerly Ellen Seidler at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. It was written by Paul Grabowicz and edited by Pamela Reynolds and Richard Koci Hernandez and Manjula Varghese.

Copyright UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism . Any code samples in these tutorials are provided under the MIT License

The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.

THIS PAGE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE INFORMATION IN THIS PAGE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THIS INFORMATION.